Acid Horror History #4 - Life is a Nightmare: Sigmund Freud, The Sandman, and Phantasm (1979)

I’ve asked the question; What is Acid Horror? But now I want to explore it, prod it like a surgeon with a knife - pick apart the bits and pieces that make it up. Join me for this retrospective series of short essays as we explore the media which inspired the term ‘Acid Horror,’ and more importantly… what the subgenre can teach us about ourselves.

_________________________________________________________

Death is a part of life. It may be the last part, the part that we try to avoid and vigorously deny, but from the moment we learn of its existence as children, Death remains with us.

I don’t remember how old I was the first time I saw Phantasm (dir. Don Coscarelli, 1979), but it must have been somewhere in my mid teens. I was old enough to have read Dune, and to have recognized the Litany Against Fear as it was sort-of quoted in the fortune-teller scene, but young enough that I spent most of the next day trying to use Forge Mode in Halo 3 to turn one of the multiplayer maps into Morningside Funeral Home. It didn’t really work, but it was something to do.

My step-father got the DVD through Blockbuster’s mail-in rental service (or was it early Netflix?) and smiled like a misbehaving kid when he asked if I had ever seen it. As a certified monster movie buff, I was all too eager. This was, after all, the man who had shown me Alien, The Thing, The Fly… but also, hilariously, a deservedly-forgotten Disney film called The Gnome-Mobile.

No matter how old you are, or how much you think you know what to expect, the first time you watch Phantasm will always surprise you. It certainly surprised me. We watched it together, delighted in all of the bizarre imagery its fans have come to know and love, and soaked up all of the strange, surreal atmosphere the film was so effectively creating. It was, and is, a movie born from nightmares with a poignant beating heart at its center; the childhood fear of death, both for yourself and your loved ones.

There was more for me to connect to, too. Like the main character Mike, I was the scrawny, annoying younger brother to a taller, cooler older brother, and even though my brother didn’t watch the movie with my dad and I, it was like he was right there with us every time Jody was onscreen.

Now that my father and my brother are both dead, I can’t think of Phantasm without thinking of them.

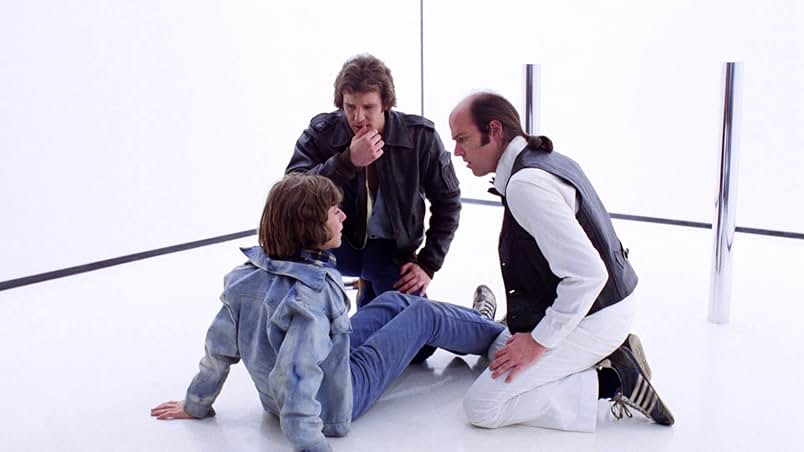

Phantasm, loosely, is the story of a kid, his brother, and their friendly neighborhood Ice-Cream man fighting the embodied concept of death. The kid, Mike, has been struggling in the aftermath of their parents’ death, especially as his brother Jody eyes the promise of the open road and a life without Mike always tagging along. After the death of their friend Tommy, who was in a band alongside Jody and Ice-Cream Man Reggie, Mike begins to suspect that the local undertaker is hiding a dark secret. As it turns out, the Tall Man is hiding several.

As surreal as the film is, as many rug-pulls and dream reveals as it stacks on top of one another, Phantasm fleshes out a simple, nightmarish idea in a complicated way. Like the best horror and science-fiction, it creates an ontology - a set of concepts and their relations to each other - that has a robust internal logic. Each element of horror is a branch of the same tree; that death is both familiar and frighteningly unknown. It builds the imagery of death into a mythology - the undertaker into Death embodied, the embalming process into alien surgery, the processed bodies into hideous, shrunken caricatures of the human form, and the brain of the deceased into a disembodied, sterile sphere of pure aggressive impulse.

The idea of a synthesis of nightmarish horror and rudimentary science-fiction, while revolutionary, is not new. In fact, Phantasm began its development process as a planned adaptation of Ray Bradbury’s Something Wicked This Way Comes, before the rights to Bradbury’s book were purchased by Disney. However, almost two centuries earlier, E.T.A. Hoffman’s short story The Sandman told a similar story about a boogeyman that embodied a childhood fear, one underpinned by elements of weird science, nightmare logic, and a sense of shimmering, almost porous reality.

Written in 1816 by the man who wrote The Nutcracker and The Mouse King in the same year, The Sandman tells the story of Nathanael, a young man who is convinced that his childhood boogeyman has returned to haunt him in his adulthood. He begins to see the Sandman everywhere, embodied in a glasses salesman named Coppola that he thinks looks exactly like his childhood landlord Coppelius, who once claimed to be the mythical Sandman and threatened to pluck his eyes out for spying on the bizarre experiments Nathanael’s father and Coppelius were regularly engaged in. Their goal? The creation of artificial mechanical life. Years later, as Nathanael’s grip on reality slides further and further, he discovers that the woman he loves may in fact be one of these sophisticated automatons herself.

The story is soaked in complex psychological subtext and half-realized menace, while characters’ identities and motivations remain tantalizingly unclear through the clouded lens of Nathanael’s troubled perception. Is Coppola the same man as Coppelius, and are either of them the nightmarish Sandman? Is his beloved nothing more than a complicated trap set for him since his childhood?

In his 1919 essay The Uncanny, Sigmund Freud uses Hoffman’s Sandman to describe and examine a specific type of horror; one that modern readers may be familiar with through the term ‘The Uncanny Valley.’ The Uncanny, as defined by Freud, is the feeling of confusion and fright that occurs when we look upon something unfamiliar in a familiar way. As examples, he uses ideas like the doppelganger and the automaton; imitations of human form without fully human function, whose imperfect shape and limited range of motion set off the same part of our brain that once warned our ancestors of an unseen predator. For something to be uncanny is for it to be ‘wrong,’ in a hard to define way, like a corpse covered in makeup that was once a family member. They still look like themselves by any measurable metric, but something deep inside our brains knows they have been rendered permanently different. And if they moved, or spoke…

The Tall Man, with his shrunken bodies, spheroid brains, and yellow embalming-fluid blood, is the uncanniness of death personified. And if we take the fourth Phantasm film as gospel, he is a doppelganger too - only one in a line of artificially-created extradimensional duplicates of a human inventor from the 1800s named Jebediah Morningside.

The Tall Man we meet in the first Phantasm is too tall, too long for his clothes, grasping at the young Mike with the gnarled, bony hands of the Grim Reaper himself. And as any mortal man will tell you, you can’t beat death. You can shoot him, stab him, cut off his fingers, run his car off the road, blow up his funeral home, even trick him into falling down a bottomless mineshaft, but Death never stops… and it’s never delayed for long.

When you wake up from your nightmares and clutch your covers tight, you may try to tell yourself that monsters aren’t real, but that isn’t strictly true. What Freud, Hoffman, and Coscarelli all capture is a bleak sort of universal truth - that the monsters of the real world have unclear boundaries, fluid forms, and unstoppable, all-pervading influence. The horrors of biological life are almost exclusively uncanny. But if Death, if trauma, if madness has a face, even one which horrifies us, it can be fought. If two brothers and an Ice Cream man can face death, not without fear but without hesitation, then so can we. Can it be overcome?

Maybe only in our dreams.

SOURCES:

Phantasm (dir. Don Coscarelli, 1979)

The Sandman (E.T.A. Hoffman, 1816)

The Uncanny (Sigmund Freud, 1919)

All images sourced from IMDB